This is a blog post by Drea Knufken.

Financial crises are consistent in one way, and one way only: They’re far more sexy when your neighbors are wearing them. When you suffer your own, runaway inflation becomes infuriating rather than exotic, and bogus bank scams go from intriguing to fist-clenching.

It’s all fine and well until it hits you squarely across the jaw. Which is what the people who run (or, more aptly, misguide) the United States have just done to the general population. For all the progress we’re making, a purple elephant might as well be running the show.

Which leads to a deeper question. Namely, does anyone run the show during a financial crisis? Is there any way to skip out of one as quickly as it enveloped you? Check out these ten nasty crises, and see for yourself:

10. Swedish Financial Crisis (1990-1994)

Cause: In 1985, Sweden deregulated its credit market, leading to a commercial property speculation bubble. Between 1990-94, the bubble burst, leaving 90% of the banking sector with massive losses, including all of Sweden’s largest banks.

Action: The government bailed out banks that looked like they could eventually survive the crisis, nationalizing two of them. It also extended a guarantee to those banks’ creditors, which kept consumer confidence up.

It let the banks destroyed by the crisis fail. Though the government took on bad assets worth about $9.9 billion, it was eventually able to recoup the losses through dividends and reselling assets from the nationalized banks. Stockholders were left empty-handed, but taxpayers didn’t have to foot the bailout bill.

Hear that, United States?

Moral of the story: Don’t save stockholders if you can save taxpayers. Investors, who take calculated risks by investing in the stock market, are in a position to bear losses with partial responsibility. Taxpayers, meanwhile, should not be punished for someone else’s oversights.

9. United States Savings and Loan Crisis (1986-1989)

Cost: $160.1 billion ($124.6 billion taxpayer money) and 747 United States savings and loan associations.

Causes: Policy expert Bert Ely says old, incompetent policies were behind the mess.

Among them:

-The government picked S&L’s, traditionally funded by short-term deposits, to finance long-term, fixed-rate mortgages. Whenever short-term interest rates went up, S&Ls lost money on their long-term mortgages, leading to negative mortgage interest rate spreads.

-The S&L industry was subject a Depression-area regulation limiting the interest rates banks could pay on their deposits. To keep interest costs under control, S&Ls used funds from savers to cover home buyers, earning interest income on ten- to twenty-year-old fixed-rate mortgages through what Ely calls “maturity mismatching”.

-Restrictions on interest rates stuck S&Ls with rates below market value. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which kept interest rates for homebuyers low, limited S&Ls’ profits–another reason they relied heavily on maturity mismatching to make a profit.

When Chairman of the Fed Paul Volcker restricted the dollar’s growth in the early ‘80s to combat stagflation, interest rates skyrocketed, and the S&L industry collapsed.

Action: The Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act (1989), which created two new oversight agencies, a new insurance fund for thrifts, and a trust corporation to get rid of the zombie institutions that regulators had taken over. Additionally, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were given more responsibility in supporting mortgages for families in need.

Moral of the story: When the government puts impossible restrictions on a bank’s ability to make money, the bank finds a workaround to keep its bottom line working. When the Fed makes a change that blows the lid off the bank’s workaround, the whole system collapses.

8. Northern Rock Bailout (Great Britain, 2007)

Image: Dominic Alves/Flickr

Causes: Financial services expert Martin Upton says that when vast numbers of mortgage holders with bad credit in the United States defaulted on their loans, financial institutions around the world became cautious about lending one another money. After all, nobody was sure how much money their exposure to the US subprime crisis would lose them.

As a result, liquidity around the world went down, while interest rates went up. Unlike the United States, the Bank of England did not flood the markets with billions of dollars to get liquidity back up. Banks were, for the most part, on their own.

Enter Northern Rock. Northern Rock’s lucrative mortgage business (comprising about 40% of company assets), was located in a company in the (tax-sheltered) Channel Islands called Granite.

Granite was a charitable trust set up to benefit a Down’s Syndrome charity. However, Granite never donated any of its £45 billion of assets to the charity. Instead, it acted as a securitization vehicle, selling “asset-backed securities” to investors and replacing maturing mortgages with new ones.

When global liquidity dried up, Northern Rock couldn’t cover its money market borrowings. It asked the Bank of England for money in 2007, at which point the Tripartite Authority gave it emergency financial support.

After the bailout news hit, customers Martin Upton”>ran on the bank, withdrawing about £1 billion, or 5% of Northern Rock’s total bank deposits, in one day, and up to £2 billion by September 17. Bank shares to fell 72%.

The run tapered off after the British Government said it would guarantee all Northern Rock deposits. In January 2008, Northern Rock sold its lifetime home equity release mortgage portfolio to JP Morgan, using the £2.2 billion gained from the sale to pay off part of its Bank of England loan.

In February, the government announced that it adding Northern Rock’s liabilities to the country’s national debt, now pegged at 45% of GDP. It was thus nationalized.

Action: An internal report released in March 2008 cited inadequate government supervision during the Northern Rock crisis, but blamed the bank’s collapse on its senior management.

Moral of the story: Repackaging debt as assets in a fake nonprofit only works when the economy is going smoothly. Don’t build your entire business out of this practice and expect to survive.

7. Tulip Mania (The Netherlands, 1637)

Causes: The first speculative bubble on record revolved not around property or companies, but around tulip bulbs. After tulips were introduced by modern-day Turkey to Europe in the mid-1500s, people in the Netherlands grew especially fond of them, seeing them as a status symbol.

Tulips infected with a certain virus tended to develop spectacular colors, flames, and lines on their petals. These new varieties were given high-sounding names and coveted wildly by the population. In order to secure these fancy tulips in advance—tulips with the virus can take as long as 12 years to develop from seed to flower—a market developed around their trade.

Traders signed medieval futures contracts that guaranteed them tulips at the end of the season. Professional growers, meanwhile, were willing to pay more and more for the popular flowers. Some tulips were worth more than peoples’ annual wages.

In the 1630s, speculators, lured by tales of sudden riches, flooded the market. The Dutch government banned short selling of futures contracts several times in the 1600s to control the mania. It also created a formal market for purchase and sale of tulip futures, requiring traders to meet in taverns and pay a small fee for each trade.

Bulb prices climbed until early 1637, when tulip traders were no longer able to sell bulbs at inflated prices. Demand collapsed, leading to a drop in price. The tulip futures trade stopped.

Action: Tulip speculators went to the government for help. The government, in turn, permitted futures contracts to be voided with a 10% fee. Many futures holders voided their contracts, and bulb sellers were stuck with their inventory.

Moral of the story: People go crazy when they become convinced that they can get rich quickly. Even off a tulip bulb future.

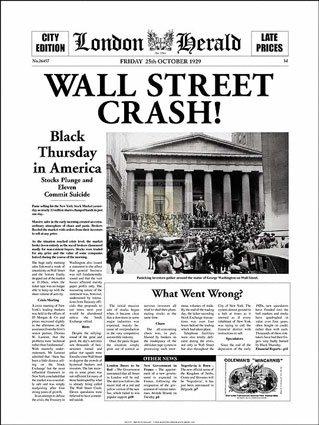

6. Wall Street Crash of 1929

Cause: In the late 1920s, hundreds of thousands of investors contributed to a speculative bubble in the stock market. Many went into debt to purchase stock, resulting in more than $8.5 billion in debt throughout the nation—more money than was in circulation at the time.

When the market turned bearish on October 24, 1929, investors panicked, causing a massive selloff that tanked the stock markets and contributed to the Great Depression of the 1930s.

To demonstrate confidence in the market, the Rockefeller family and the heads of major banks bought large quantities of stock. This move didn’t stop the panic. During the week of October 24, the market lost a total of $30 billion, more than the United States had spent on World War I.

The stock market crashed caused businesses to close, mass layoffs, and a rash of bankruptcies. An international run on the dollar resulted in increased interest rates, driving out around 4,000 lenders.

Action: After an investigation, Congress passed the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 (now repealed), mandating a separation between investment and commercial banks. They believed this would avert another dramatic panic sale. It didn’t—the Dow fell 22.6% in 1987—but, to date, the Great Depression that followed the 1929 crash hasn’t been repeated.

Moral of the story: Don’t panic. Many scholars now say that the 1929 crash didn’t cause the Great Depression, but certainly contributed to its severity. Public panic only makes situations worse than they already are.

5. The Japanese asset price bubble (1986-1990)

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Causes: After World War II, Japan’s domestic policies encouraged people to save money. People put more money into banks, making it easier for companies to take out loans and lines of credit.

Using their new lines of credit, Japanese companies invested in capital resources, enabling them to produce goods more efficiently than international competitors. Japanese provided high-quality products at extremely competitive prices, becoming a major world economic power in the process.

At the same time, the yen steadily appreciated. Investors to make good money off financial markets. People used easy credit to develop property and buy homes, contributing to a speculative real estate bubble.

Real estate prices inflated, with some Tokyo properties selling at $139,000/square foot. Stocks prices seemed to have no ceiling at all. Reinvestment expanded the economy further. The Nikkei reached an all-time high of 38,957.44 in December of 1989.

Then, in the early 1990s, Japan’s bubble started to sink. Rather than a dramatic crash, real estate and stock values decreased slowly, leading to Japan’s “lost decade.” People started investing outside of the country; companies lost some of their competitive advantage internationally as a result. Low consumption rates coupled with lower output and employment meant steady deflation.

Action: The government lowered interest rates to practically nothing, which did nothing to encourage Japanese people to put money in the banks. The government subsidized banks and businesses on the brink of failure, effectively propping up zombie organizations with little visible benefit to the economy. The Yen carry trade became one of the main ways people made money off their investments.

In 2003, the Nikkei finally started climbing again.

Moral of the story: When bubbles grow, they’re wonderful in every way. When they sink—and they can sink, rather than popping—they can set the economy back more than a decade.

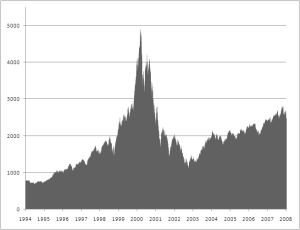

4. The .com bubble (1995-2000)

Cause: In the mid-1990s, a new type of business emerged: The .com, a company either based solely on the Web or servicing the Internet, its people, and its technology. When early .coms’ stock values shot skyward, venture capitalists jumped aboard en masse to finance Internet startups.

A .com’s lack of a viable business plan didn’t stop many VCs from throwing in money. Investors and startup executives assumed that once a .com had peoples’ attention, the money would come organically in the future.

Speculators jumped in, creating a market full of wildly overvalued startups. Lavish spending and astronomical publicity campaigns followed. .coms burned through their VC money, positive it would come back soon. Day trading became a relatively common way to make fast money.

In 2000, the NASDAQ began to trend downward, leading to what’s known as the .com bust.

Action: Though the government didn’t address .com startups or speculation, its policies and timing may have contributed to a loss of confidence. Between 1999-2000, the Fed increased interest rates six times in order to reign in the economy. Around the same time, a flurry of government investigations stalled corrupt business practices.

For example, around the same time the NASDAQ began its slide, Microsoft was declared a monopoly. Major telecommunications companies, such as MCI Worldcom, toppled under debt and management scandals. Regulators put the financial industry under fire for misleading investors during the .com boom. Famously, Enron collapsed after investigators uncovered an accounting scandal.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act was passed in 2002, laying out far tougher transparency and accountability standards for public companies.

Moral of the story: The market, your favorite bipolar uncle, likes to celebrate wildly when he finds out about new technology. Just be sure to steer clear of him when his mania turns into prolonged, howling grief.

3. 1997 Asian Financial Crisis (1997-1999)

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Causes: In the years leading up to the crisis, Southeast Asia was a hot international investment destination. ASEAN countries’ high short-term interest rates gave foreign investors favorable rates. Capital flooded into the region.

Asset prices increased, and growth rates in the early 1990s were as high as 12% of GDP, leading analysts to refer to the phenomenon as the “Asian Tigers” and “Asian Economic Miracle.”

At the same time, Thailand, South Korea, and Indonesia ran huge deficits. They borrowed quite a bit of money externally; keeping their own interest rates fixed encouraged this behavior. This left them vulnerable to changes in foreign markets.

In the early ‘90s, foreign investors turned away from Asia. Higher US interest rates valued the dollar up, which in turn made Southeast Asia’s exports less competitive (their currencies were pegged to the US dollar). Southeast Asian exports slowed in early 1996, fueled at least in part by China’s increased competitiveness in the export market.

What caused the crisis from here is subject to rampant debate. Some say that policies leading to large amounts of credit pushed up asset prices, which then collapsed, leading to massive debt defaults (kind of like the subprime crisis).

International investors panicked and withdrew credit. To keep the region attractive to foreign investors, ASEAN governments jacked up interest rates and bought up excess domestic money using foreign reserves. As a result, the governments’ central banks started running out of foreign reserves, while capital continued to drain from the region.

In 1997, Thailand’s government decided to float the baht, unleashing what’s now known as the Asian Financial Crisis. Regional currencies depreciated, meaning liabilities denominated in terms of foreign currency grew even more expensive in domestic terms. Entire economic sectors melted down, while people fell into poverty. Stock markets and currencies rapidly devalued. Politics destabilized, with executive resignations and an increase in extremist groups. The region seemed to melt down in the blink of an eye.

Actions: The International Monetary Fund created bailout packages dictating reforms in exchange for debt defaults. The reforms included cutting government spending, allowing banks to fail, raising interest rates, and becoming more transparent.

The IMF’s actions had questionable results, leading to a backlash against powerful international NGOs that continues today. Some say the crisis in Asia also contributed to the recent United States housing bubble.

Moral of the story: When things crash, rich people may interfere, offering money in exchange for an agenda. That doesn’t mean their agenda is right, or even useful. Moral #2: Financial meltdowns can happen at the speed of light.

2. Russian financial crisis (1998)

Image: Kremlin.ru

Causes: In 1993, the Russian government came up with inflation-free short-term treasury bills, known as GKOs, to finance the country’s deficit. GKOs were traded on currency exchanges. Though mostly state-owned, roughly 1/3 of funding came from foreign speculators, which they attracted through high interest rates. The government used proceeds from sales of new GKOs to pay off interest on matured bills—a classic Ponzi scheme.

In June 1997, looking to raise capital, the government increased GKO interest rates to 150%. By the beginning of 1998, GKO interest payments comprised more than half the federal government’s revenue. They became large domestic banks’ main source of revenue.

Meanwhile, the government owed workers roughly $12.5 billion in unpaid wages. It was also making more money from GKOs than from taxes. Investors lost confidence in the Russian government when they put all the pieces together, selling Russian securities and rubles. The Central Bank tried unsuccessfully to stabilize the ruble by spending an estimated $27 billion of its United States dollar reserves.

In August 1998, Russia’s markets collapsed. Investors, fearing a devaluation of the ruble and a debt default, panicked, leaving the market with a 65% drop in one day. As a result, several major banks closed, and inflation increased. It also eradicated the nascent middle class by eating through peoples’ bank savings.

Actions: The government cut spending on social- and municipal services. Fortunately, oil prices skyrocketed after 1999, facilitating a quick recovery.

Moral of the story: Don’t anger people while financing yourself with a Ponzi scheme. It ends up being much more expensive in the long run.

1. Argentine economic crisis (1999–2002)

Causes: Agentina had a history of volatility when the 1980s Latin American crisis struck. The import-dependent country was running low on US dollars, a currency that people were entitled to convert their pesos into if they felt like it (this was a “safe” option for many people).

The country also had a history of runaway inflation and associated loss of confidence in its currency. Meanwhile, the government spent lavishly on itself while ignoring the country’s crumbling industrial infrastructure.

In the 1980s, Mexico and Brazil, major Argentinian trade partners, suffered economic crises that spread through Latin America. Brazil’s real was devalued in 1999, hurting Argentine exports; at the same time, the dollar was revalued, delivering the Argentinian peso another blow.

In 1999, the country entered a 3-year recession. The government did not devalue the peso or unpeg it from the dollar, making the crisis worse.

The recession deepened. Investors ran on banks for dollars, which they then sent abroad for safety. In response, the government more or less froze everyone’s bank account.

Citizens protested in major cities, eventually starting fires and destroying property. Violence and fatalities ensued. In 2001, the government collapsed. People bartered for goods because they lacked cash. Business shut down. Many people eked out a living by scavenging cardboard for recycling plants.

Action: The government at first tried to set up a third currency between the peso and the dollar, but this failed. It then mandated that all dollars in banks be converted into pesos.

The exchange was left to float, leading the peso to depreciate. Exports became more competitive. The government tightened its tax policies, improved social welfare, encouraged business growth, and put reserve dollars up for sale on the market. As worldwide demand from Argentinian agricultural products increased, the country grew a trade surplus. It continues to struggle with inflation, however.

Moral of the story: Freezing bank accounts is a really bad idea.

Drea Knufken is a freelance writer, editor, ghostwriter and content strategist. Her work has appeared in national publications including WIRED, Computerworld, National Geographic, Minyanville, Backpacker Magazine and others. For more information, please visit www.DreaKnufken.com. You can also find Drea via her blog, Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter.