From the Industrial Revolution onwards, people have toiled for too little money in cramped conditions, often under abusive conditions. The phenomenon has expanded worldwide and products made in sweatshops have expanded from mere clothes to all manner of commodities, from seafood to virtual video game gold. Here’s a look at fifteen of the most infamous sweatshops of the last 200 years.

“The Satanic Mills,” Leeds, 19th century

In 1801 there were only about 20 factories of any sort worldwide. By 1838, there were 106 wool mills in Leeds alone, employing some 10,000 people. Symbolic of the English Industrial Revolution at its most inhumane, the unregulated workshops were literally deadly. A child died in 1832 after not being allowed to so much as go to the bathroom. Dubiously immortalized by William Blake as “these dark Satanic mills.” The declining wool industry was supplanted in the 1850s by the new ready-made clothing industry, which in the 1880s employed mostly Jewish immigrants. Most of them had just intended to stop and earn some cash on the way to the United States, but ended up working in terrible conditions simply because it was better than life in Russia.

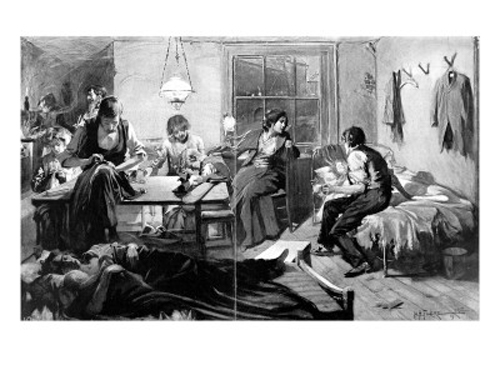

London’s West and East End, 1850

By 1850, Factory Acts (Britain’s labor laws) had already cut down the number of hours children could legally work. British clergyman and agitator for social reform Charles Kingsley railed by creating the 1850 pamphlet “Cheap Clothes And Nasty.” “Kingsley described in detail the conditions and compared the clothing laborers to slaves. They were largely brought over from Ireland for a fee, and forced to labor away in rooms where the ceiling was too low to stand all the way. “If these men know how their clothes are made, they are past contempt,” he said of their customers, “it is their sin that they do not know it.” Sound familiar?

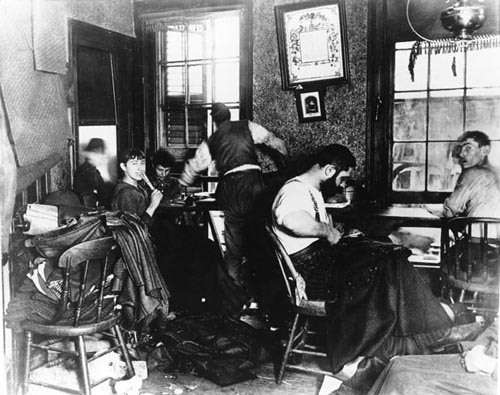

“The Sweaters of Jewtown,” Ludlow St., New York, 1890

As a boy, Jacob Riis read James Fenimore Cooper and Charles Dickens and dreamt of America. Upon his arrival 1n 1878, however, Jacob found himself smack in the middle of a depression and spent three years living in the direst poverty. In 1878 he began working as a police reporter, giving him increasing familiarity with New York City’s direst areas. The invention of flash powder gave him the tools to take elegant photographs to go alongside his Dickensian prose to create an unabashed plea for having mercy on the poor. The result was his 1890s landmark volume, “How The Other Half Lives”. The most famous story told in the book was a chapter entitled “The Sweaters of Jewtown.” In which he exposed the inner workings of New York’s garment industry.

Packingtown, Chicago, 1906

In 1904, 26-year-old failed novelist Upton Sinclair had penned four flops to his name. However, when he received a $500 advance for a serial about wage slaves in Chicago’s meat-packing district, his career path changed. He immersed himself in the meat-packing industry for seven weeks, sneaking in shabbily dressed enough to be granted entry. Thumbs were hacked off, blood covered the slaughterhouse floors, and gore shot out of diseased cattle. Sinclair intended his novel to promote socialism, but it was more effective as a catalyst for food production reform.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, New York City, 1911

On March 25, 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory caught on fire. The Factory, located on the top three floors of a ten-story building in New York City, 145 employees diedin the blaze, largely because one door had been locked. One of the factory’s owners would routinely lock to the door to prevent employee theft, which is what he was said to be obsessed with. At the trial, the owners were acquitted of wrongdoing, as it couldn’t be proven they knew the door had been locked. Twenty-three individual civil suits returned an average of $75 per life lost. The fire was the deadliest industrial accident in New York City history and led to the establishment of the Factory Investigating Commission, which helped implement 36 important labor reform laws from 1911-14.

Peace Market, Seoul, 1970

As manufacturing began to expand through Korea in the 1960s, workers were often treated more as assembly robots than human beings. A fed-up 22-year-old Chon Tae-il lit himself on fire after shouting “Workers are not machines!” to protest the appalling textile factory conditions at the nearby Peace Factory. Talk about going out with a bang.

Manhattan Chinatown sweatshops, 1980s

Manhattan Chinatown sweatshops emerged in the 1940s as the cheap rent of Chinatown attracted thousands of migrant workers. There workers are paid by the piece rather than hourly; in the early 1980s it was as little as eight cents a piece (one 90-year-old woman was found working for a dollar an hour). That was also the point at which the Reagan government took a strong interest in prosecuting. The sweatshops have never really gone away, thriving on energetic labor from China looking to send money back home.

El Monte, California, 1995

Seventy-two Thai laborers were freed from an apartment complex sweetshop in El Monte, California in 1995. They had left Bangkok to seek opportunity in Los Angeles. Many of them leaving behind jobs with reasonable 10-hour days, a reasonable salary and weekends off. In El Monte, they slept ten to a room with boarded-up windows and force to work exhausting amounts. The perimeter was cordoned with razor wire. Enough workers managed to escape to alert Thai and American authorities, who shut down the complex.

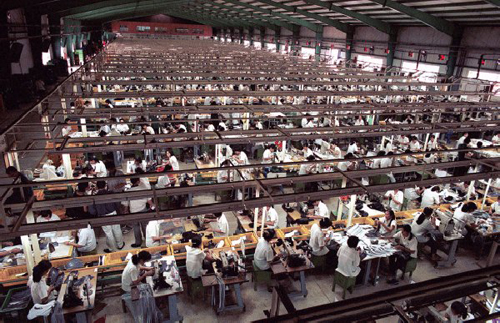

Nike sweatshops, Asia, the 1990s-onward

As liberal students dragged anti-globalization/sweatshop concerns into the front of the public’s consciousness, no company received more heat for their labor practices than shoe manufacturer Nike. Led by assertive, largely unapologetic CEO Phil Knight, Nike played strong defense. They have pointed out that workers in Indonesia saw their minimum wage rise from under a dollar a day to over two in part to multinational hiring by companies like Nike and have told stories about Vietnam workers waiting outside the factory doors, hoping someone would quit so they could get a job. Eventually, all the bad publicity caught up with them and the company set up internal monitoring over outsourced labor, working with protest groups to investigate claims of any abuse, mitigating ugly public pickets.

Kathie Lee Gifford’s Honduran/New York sweatshops, 1996

After Nike, Kathie Lee Gifford suffered one of the more intense shamings for her involvement with sweatshops. During congressional hearings, Kathie Lee faced accusations that her Walmart factory line was made at Global Fashions, a Honduran sweatshop. Global Fashions employed 5-year-old girls for 75-hour work weeks, at the grand wage of 31 cents an hour. She promptly took to the TV cameras to cry, creating an indelible cautionary image for the clothing industry. Soon after, it was revealed even more Kathie Lee laborers were working in a New York factory that hadn’t been paid in weeks. At that point, husband Frank took over, showing up with news coverage and $9,000 in cash. Such repeated embarrassments led to the formation of the Fair Labor Commission, as much as to avoid public humiliation as to do right by workers.

Toyota, Tokyo, 2002

Toyota’s manufacturing processes came under scrutiny in 2002 after one Kenichi Uchino collapsed and died on the Tokyo factory’s floor in his fourth hour of “voluntary overtime.” In his last month there, he’d worked 106 hours of overtime, largely unpaid — a standard practice in Japan, where employees are judged on their loyalty and dedication. The term “karoshi” (death from overwork) describes just such a situation, as a court ruled in favor of Uchino’s widow five years later. Toyota has since limited overtime to 360 hours a year, though the workers respond by sticking around with the lights off.

Election Machines & Systems, The Philippines, 2006

The State of Florida drew heat in 2007 when Dan Rather reported that defective voting machines used during the controversial 2000 presidential election in Sarasota were assembled in sweatshops in Manila. Workers earned from $2.15 to $2.50 an hour to assemble $3,000 voting machines, often at temperatures of over 90 degrees. Their most strenuous quality control test was shaking some of them to make sure no loose parts were rattling around. Company officials sold these expensive machines knowing full well some wouldn’t respond.

“Gold Farmers,” Wuxue, China, 2006

One of the stranger new forms of sweatshops came through the immersive computer game, “World of Warcraft.” The game is notoriously time-consuming. In 2006, reports surfaced of a sweatshop dedicated to earning virtual currency for items in the game. Chinese men worked 8 to 10 hours a day with one day off a week, for $100 a month. The gold they earned was sold for much more. In the town of Wuxue, some 20 other game-playing firms sprung up, some employing as many as 200 people. The game companies aren’t amused, shutting down the accounts whenever they’re discovered. They have not managed to shut down the market though; new accounts are simply opened and business opens up once again.

Olympic Sweatshops, 2007, China

As China prepared to put on its best public face to the world with the 2008 Beijing Olympics, reports arose of sweatshop factories being used for Olympics-related merchandise in at least four different places. Twelve-year-olds worked in double shifts, workers were docked a full day’s pay for spending more then 15 minutes in the toilet, and no protection from paint vapors or dust was provided. Beijing authorities responded, per usual, by not doing anything and just getting on with business.

Squid sweatshops, Santa Rosalia, Baja California, 2010

Just as sweatshops have evolved for the digital age, a sweatshop need not be solely an indoor institution. In Baja California, men fish for squid for 10 hours at a time for $50. On shore, workers sleep on filthy factory floors while waiting for the squid, which has to be processed in a location with two toilets for 80 workers (cleaned once a week, and rarely with any toilet paper in there). The squid is sold to Korea and China, and will continue to be produced under unsafe conditions as long as seafood importers don’t have to have transparent transactions.